- Home

- Robin Cook

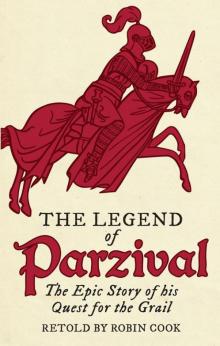

The Legend of Parzival: The Epic Story of His Quest for the Grail

The Legend of Parzival: The Epic Story of His Quest for the Grail Read online

Preface

The tale of Parzival and his search for the Holy Grail has endured for centuries. Today he may be more familiar as Sir Percival, one of King Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table, yet Wolfram von Eschenbach’s thirteenth-century epic poem Parzival is one of the earliest versions of the story and is a classic of medieval German romance. The themes of love, compassion and spirituality remain timeless, yet to the modern-day reader, Eschenbach’s text – sixteen books, each comprising several thirty-line stanzas of rhyming couplets – may seem daunting, whether read in the original Middle High German or in any of the many translations that exist. Other difficulties in approaching the story include the unfamiliar conventions of medieval storytelling and the plethora of names and places, some recognisable, some not. In the version of Parzival that you are about to read, I have attempted to make Eschenbach’s vision accessible to the new, modern reader by telling this incredible story as just that: a story. I remain faithful to the plot, structure and themes, but there are no rhymes or impenetrable medieval language here. I am sure those who already know the poem will probably take exception to some of the liberties I have taken – that always happens – although some readers who know Wagner’s operatic version, Parsifal, might also be surprised at some of the liberties he took. Yet I hope that readers will not take this simply as a substitute for Eschenbach’s poem, but rather as inspiration and encouragement to read the original of this extraordinary tale.

Readers who already know something of Arthurian legend will be well prepared for Parzival’s mixture of realism, magic and coincidence. Yet there are occurrences that modern readers may find odd. Modern-day readers may find the description of Feirefiz’s black-and-white skin to be odd, perhaps even racially insensitive. Eschenbach almost certainly didn’t intend it as a comment on race, but to symbolise deeper meanings relating to the power of intellectual knowledge, which at that time was far more developed in the Arab world than in Europe. Another example of something that may seem strange to modern readers is when we discover that Parzival’s friend, Sir Gawain, has not seen his mother or sisters since he was sent off to train as a squire; however, this was not unusual in the twelfth century. Neither may readers be conversant with the rules of courtly love. Choosing our partner is something we take for granted now, yet in those days it was much more complicated. How a lady and her knight behaved towards each other had rules.

There may also be unfamiliar aspects for readers who know other versions of the story. In Eschenbach’s account – here there is more confusion – the Grail Knights are quite different from the Knights of King Arthur. In fact, in Eschenbach’s Parzival, King Arthur is a somewhat distant and, at times, ineffective figure. Those of you who know the story of Sir Galahad might find this unexpected – in some accounts, Galahad is the Arthurian knight who succeeds in the quest for the Grail – but in fact the Galahad story is a much later version of the legend.

As Eschenbach’s Parzival goes on, more and more of the characters seem to be related to each other. Some editions of the text have genealogical tables to show family structures, but it is more in the spirit of the story to consider them allegorically, in a way that provokes thought about what these close relationships between characters mean. One can also apply interpretation and guesswork to the origin of the story. It is in part Celtic myth, but it has Biblical connections too. There are also ties to the troubadours of the Languedoc region and the Cathars who lived close to Eschenbach at that time. There is even speculation over the nature of the Holy Grail: nobody is sure what it really is, although we certainly find it used as a metaphor in any newspaper. Some think it comes from a Celtic bowl of plenty; others say it was the cup that Christ drank from at the Last Supper and caught his blood when his side was pierced on the cross; others say it was a jewel struck from Lucifer’s crown when St Michael expelled him from Heaven. Eschenbach’s Parzival does not help much: in the text, sometimes the Grail is referred to as a stone, sometimes even a ‘thing’. Yet we know it is our hero’s goal and an object of awe and power, even if its form and meaning remain elusive.

This also applies to the locations in the text: some are recognisable, for example, Sicily, Nantes and Anjou, but we are not sure about Patelamunt and Zazamanc or whether they have real-life equivalents. The story weaves in and out of the worlds of fact and imagination. Being in part an allegory, this means that sometimes events are not supposed to be understood too literally. At the same time, don’t expect a neat interpretation that everything fits into. I have heard and read many different approaches to this story: they are all interesting and one interpretation does not preclude another.

There is much to ruminate on and discuss, and you will find plenty of literature if you want further comment and interpretation. But a good place to start would be Eschenbach’s original account – and then you can decide if I made a decent job of this.

Good reading!

Robin Cook

List of Main Characters

Anflise Queen-widow of France and Gahmuret’s former ‘Lady’

Anfortas The Fisher King, King of Montsalvaesche, and Parzival’s uncle

Antikonie Sister to King Vergulacht of Ascalon

Arnive Queen, and King Arthur’s mother

Belacane Queen of Zazamanc, Gahmuret’s first wife and mother of Feirefiz

Bene Daughter of the ferryman at the Castle of Wonders

Clamide King besieging the castle of Condwiramur

Condwiramur Wife of Parzival, cousin of Sigune and niece of Gurnemanz

Cundrie la Sorciere The Grail Messenger

Cundry Sister to Gawain and later wife to Lischois Gwelljus

Cunneware Sister to Duke Orilus

Feirefiz Parzival’s half-brother, son of Gahmuret and Belacane, later married to Repanse de Schoye

Gahmuret Husband to first Belacane and then Herzeleide, father to Feirefiz and Parzival

Gawain Knight at Arthur’s court, son of Sangive and nephew of King Arthur, brother to Itonje and Cundry, later married to Duchess Orgeluse

Gramoflanz King, guardian of the Tree of Virtue, later husband to Itonje

Gurnemanz Parzival’s tutor, father of Liaze, uncle to Condwiramur, grandfather of Schionatulander

Herzeleide Gahmuret’s second wife, Parzival’s mother, also sister to Anfortas, Trevrezent and Repanse de Schoye

Isenhart Knight slain in the service of Queen Belacane

Ither of Gaheviez The Red Knight, slain by Parzival and cousin to him

Itonje Gawain’s sister, in love with Gramoflanz

Jeschute Wife of the Duke Orilus

Kay Knight at Arthur’s court

Kingrimursel Challenger of Gawain, cousin to Vergulacht

Kingrun Seneschal to Clamide

Klingsor Duke of Terre Merveil, a powerful sorcerer

Liaze Daughter of Gurnemanz

Lippaut Duke, father to Obie and Obilot

Lischois Gwelljus Knight in the service of Orgeluse, later married to Cundry

Meljanz King, later married to Obie

Obie Daughter to Duke Lippaut, sister of Obilot, later married to King Meljanz

Obilot Daughter to Duke Lippaut, sister of Obie

Orgeluse Duchess, loved by Anfortas, but wooed and won by Gawain

Orilus Duke, brother of Cunneware, husband to Jeschute and slayer of Schionatulander

Parzival The Grail-seeker, son of Gahmuret and Herzeleide, half-brother to Feirefiz, husband to Condwiramur

Repanse de Schoye Grail-bearer, sister to Anfortas, Trevrezent and Herzeleide, later married to Feirefiz and mothe

r of Prester John

Sangive Daughter of Arnive and sister to King Arthur, mother to Gawain, Cundry and Itonje

Schionatulander Knight to Sigune and slain by Orilus

Sigune Cousin to Parzival

Trevrezent Brother of Anfortas, Repanse de Schoye and Herzeleide, hermit, and second tutor to Parzival

Vergulacht King of Ascalon and brother of Antikonie

Contents

Title Page

Preface

List of Main Characters

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Copyright

Chapter 1

Gahmuret, tall, broad, bold and full of youthful enthusiasm, strode purposefully across the courtyard of his family’s hilltop castle. Today was the day. The castle was a hive of activity as he issued a stream of instructions to the servants who were packing his mule train. Only a month had passed since the death of his father, the Duke of Anjou, and Gahmuret was eager to take advantage of his new-found freedom. He had always known that his older brother would inherit the dukedom, so he was setting out to seek adventure in far-off lands. His mother and brother pleaded with him to stay, telling him there was plenty of adventure to be found here in France, but it was to no avail. Gahmuret was determined to find and serve the most powerful man in the world.

Accordingly they gave him a magnificent send-off, loading his mules with chests packed full of silks and velvets, cases of precious stones and fine armour. As a final gift, his mother presented him with a surcoat embroidered with his emblem, the Anchor linked with golden ropes on a dark blue background. Gahmuret made an impressive sight as he set off down the valley, his train of squires and men-at-arms stretching out behind him.

He travelled far and wide across many lands, month upon month until, after some years, he finally found the man he wished to serve – the Baruch of Baghdad, whose empire stretched for hundreds of miles. In the Baruch’s service Gahmuret achieved renown from Morocco to Persia, in Damascus and Aleppo. Throughout Arabian lands men said he was the most courageous knight ever to have ridden a horse.

On one adventure undertaken for the Baruch, Gahmuret came to Patelamunt in the kingdom of Zazamanc. As his ship came into harbour he had time to examine the city. He counted sixteen gates in the walls, and was impressed not only by the town’s fortifications but also by the huge armies arrayed both to the east and west of the walls. Many tents were assembled around the walls and all sorts of colourful pennants fluttered in the breeze.

As he disembarked, Gahmuret was met by a turbaned figure, richly dressed, who introduced himself as the marshall to Queen Belacane and enquired who he was and whence he came.

“Ah! The great Gahmuret!” he exclaimed, “I have heard of your exploits. You drove the Babylonians from Alexandria and swept the Syrians from Tyre. My queen has need of you! Please let me take you to her.”

Gahmuret readily agreed, and on the way up to the palace the marshall explained that Patelamunt was under siege from two armies. This had come about following the death of the noble Isenhart, who, in order to win the queen’s love, had taken on ever more dangerous and reckless deeds until he had been killed in her service. His followers blamed her for his death and were so stricken by grief that they had laid siege to her city.

Gahmuret entered Patelamunt to see wounded men, broken weapons and injured horses lying everywhere. The siege had taken its toll. The queen, having received warning, watched his approach from the palace window. She turned to her ladies.

“Send him rich robes and tell him to come to me. Bring some wine.”

A lady hurried off at her command and soon Gahmuret was ushered into Belacane’s presence. She offered her hand and he bowed and kissed it. She led him to a seat by the window where they could look out on the city walls, and beyond to the tents of the besieging armies. Further away, his own ship lay at anchor in the bay.

“My lord,” she said, “I have heard much of your prowess and I hope you will forgive me if I tell you of my troubles.”

“Dear queen,” he answered, “nobody has ever called on Gahmuret the Angevin in vain, if their cause be just. Who has wronged you?”

A wave of relief swept over Belacane – there was something about him which inspired her trust – and so she told him her tale.

“I took Isenhart for my knight. There was no finer man, more loyal or true, and he undertook many tasks to win my love. It is not true that I sent him to his death, but it is true that I could not immediately accept his love. That was through my own modesty, and this drove him to more and more dangerous undertakings. Eventually he even refused to wear armour when he fought. Unfortunately he challenged a knight from my own court to combat. When they charged each other, such was the violence of the impact, and so true had both aimed, that both were killed instantly. As a result, I am now besieged by two great armies. On one side Razalic of Azagouc commands the Moorish army, and on the other Hiuteger of Scotland has come, bringing forces from Normandy and Spain.”

As Gahmuret listened, he became more and more certain that he wanted to help her. As she concluded, the marshall approached and offered to show Gahmuret the positions of the armies at the sixteen gates of Patelamunt. Gahmuret turned to Queen Belacane and said, “You can be assured, gracious queen, it will be an honour to serve you in this cause.” Bowing gracefully, he turned to follow the marshall, who took him round the city walls.

Gahmuret cast his seasoned eye over the defences, noting the positioning of defensive turrets and the placing of arrow slits. The marshall showed him the jousting ground, where knights from each side met and took up challenges, and he explained how both Razalic and Hiuteger had triumphed over all who came up against them. Only by defeating them could the siege be lifted. This was the kind of contest Gahmuret relished, and he would have taken part even without the lure of the beautiful Queen Belacane.

As they returned to the Great Hall, Gahmuret ordered his squires to prepare his horses and weapons for the next day, giving precise instructions on the different manners of fighting to be expected from the Moor and the Scot. Gahmuret found himself the guest of honour at a great banquet. He was seated at the centre of the table, nobles and their ladies on either side, and he admired the rich tapestries which adorned the walls. Pages scurried back and forth bearing a choice selection of dishes, but he was actually waited on by the queen herself.

“Come,” he said, “please sit by me. I am not worthy to be served in this manner by a queen.”

“It is the least I can do to thank you for your kind assistance,” she replied, and he could not help noticing a slight blush suffuse her dark skin as she placed a cup of wine before him. However, she did sit next to him, and they listened to her minstrel, who sang songs of devotion rewarded by faithful love.

When the time came to retire for the night, he was taken to a well-appointed chamber with beds for all his squires. The queen left him, wishing him a good night’s sleep, for he would surely need all his strength on the following day. Yet it was not to be. Gahmuret tossed and turned all night long as he dwelled on the challenges to come, interspersed with thoughts of love and Belacane’s beauty and graciousness.

As the grey light of dawn filtered through the casements, Gahmuret rose, his thoughts firmly fixed on the battles ahead. His squires recognised his mood, and few words were spoken as they hurried to arm him and saddle his horse. He mounted the horse and clattered out of the courtyard, making his way to the jousting ground. There, he cantered up and down to show his possession of the field. It was not long before word was brought to Hiuteger that a new challenger had arrived.

When Hiuteger rea

ched the jousting ground, he paused and looked sharply at his opponent. “This is no Moorish knight,” he thought to himself, taking in the size of the horse, the workmanship of the armour, the design of the shield and the solidity of the knight himself. “This is a French knight, or I am much mistaken.”

The challenge was given and accepted, and the two knights circled each other before they cantered off to opposite ends of the field. Meanwhile, word of the forthcoming joust had rapidly spread. People crowded onto the city walls and soldiers from the besieging armies hurried to see how the new challenger would fare.

The trumpets sounded. Gahmuret and Hiuteger’s horses galloped, kicking up stones from the sandy ground as they charged. The crowd began to shout. Gahmuret took aim. Hiuteger covered himself with his shield, but at the last moment Gahmuret angled his own shield away, deflecting Hiuteger’s thrust, and caught him such a blow on his shoulder that he knocked him clean over his horse’s tail. A mighty roar went up from the watching crowd, urging Hiuteger to get to his feet. But Gahmuret was too quick for him: wheeling his horse, he struck Hiuteger another blow on his helmet as he tried to stand. He staggered and fell, and Gahmuret pinned him to the ground with his lance.

“Surrender!” commanded Gahmuret.

“A noble thrust!” said Hiuteger. “But who has conquered me?”

“Gahmuret the Angevin,” he replied, raising his visor.

“Your fame is widely known,” said Hiuteger. “I offer you my service.”

“Take your horse and go back to your camp. Dismiss your army. Tell them the Angevin commands it.”

Hiuteger had no choice but to obey. Yet at that moment, a distant cry was heard. All heads turned to see another knight enter the ground.

“Razalic of Azagouc now challenges you,” said Huiteger. “He is a noble Moor and a worthy foe.”

Gahmuret nodded as he examined this new challenger. “Yes,” he thought, “this will be different. The horse is a nimble Arab and will be sure-footed and quick in the turn. I must strike hard and fast.”

Shock

Shock Mutation

Mutation Chromosome 6

Chromosome 6 Brain

Brain Intervention

Intervention Invasion

Invasion The Legend of Parzival: The Epic Story of His Quest for the Grail

The Legend of Parzival: The Epic Story of His Quest for the Grail Acceptable Risk

Acceptable Risk Cell

Cell Fever

Fever Death Benefit

Death Benefit Contagion

Contagion Mindbend

Mindbend Coma

Coma Vital Signs

Vital Signs Harmful Intent

Harmful Intent Critical

Critical Foreign Body

Foreign Body Marker

Marker Blindsight

Blindsight Terminal

Terminal Sphinx

Sphinx Fatal Cure

Fatal Cure Host

Host Charlatans

Charlatans Crisis

Crisis Vector

Vector Toxin

Toxin Abduction

Abduction Viral

Viral Pandemic

Pandemic Outbreak

Outbreak Vector js&lm-4

Vector js&lm-4 Godplayer

Godplayer A Brain

A Brain Year of the Intern

Year of the Intern Outbreak dmb-1

Outbreak dmb-1 Cure

Cure Mortal Fear

Mortal Fear The Legend of Parzival

The Legend of Parzival Vital Signs dmb-2

Vital Signs dmb-2 Cure (2010) sam-10

Cure (2010) sam-10 Blindsight sam-1

Blindsight sam-1 The Year of the Intern

The Year of the Intern Intervention sam-9

Intervention sam-9 Foreign Body sam-8

Foreign Body sam-8